Directors’ and Executives’ Liabilities under PRC Company Law (3/4)

Article 192 of the new Chinese Company Law stipulates that "if a controlling shareholder or de facto controller directs a director or member of senior management to engage in conduct detrimental to the interests of the company or its shareholders, that controlling shareholder or de facto controller will be jointly and severally liable with the director or member of senior management."

(a) Defining Controlling Shareholders and De Facto Controllers Under the Company Law

Article 265 of the new Company Law defines a controlling shareholder as "a shareholder whose capital contribution exceeds 50% of the total capital of a limited liability company, or whose shareholding exceeds 50% of the total share capital of a joint stock company." The article further extends this definition to include "a shareholder whose capital contribution or shareholding ratio is less than 50%, but whose voting rights derived from their contribution or shareholding are sufficient to exert a significant influence on the resolutions of the shareholders' meeting."

The concept of a "de facto controller" is also addressed in Article 265, defining it as "a person who, through investment relationships, agreements, or other arrangements, is able to exercise actual control over the actions of the company." This definition encompasses situations where shareholders, even those holding less than 50% of the equity and not holding formal positions as directors or senior managers, exert control through investment vehicles or contractual arrangements. Article 192, read in conjunction with Article 265, provides a basis for holding these de facto controllers accountable when their actions harm the interests of the company, its shareholders, or its creditors.

(b) Application in Judicial Practice

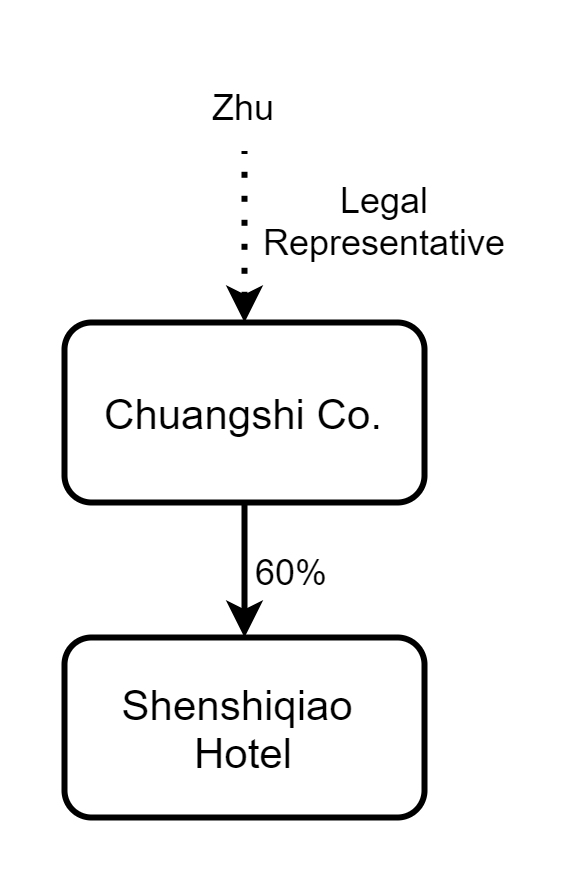

Chinese courts have considered various factors in determining who qualifies as a de facto controller. One factor is the ability of an individual authorized to represent a controlling shareholder to influence company actions through investment relationships. For example, in (2018) Supreme Court Civil Ruling 361, the court found that, because Chuangshi Company held 60% of the equity in Shen Shiqiao Grand Hotel and Zhu, as Chuangshi Company's legal representative, could control the hotel's actions through investment relations, Zhu was the de facto controller of Shen Shiqiao Grand Hotel.

Another factor considered by courts is the ability to control a company's operations through financial management. In (2017) Guangdong Civil Appeal 18696, the court held that Cao Xianghao, who had served as the company's general manager, was primarily responsible for the company’s financial matters, continued to collect debts through his personal account after the company's bankruptcy, and subsequently paid execution fees for the company in his personal name, was the de facto controller.

The practice of transferring shares to relatives, or having relatives hold shares on one’s behalf, while maintaining actual control over the company's operations, may also lead to a finding that the individual is the de facto controller.

(c) Establishing Liability

It is important to recognize that Article 192 effectively creates a cause of action akin to a tort under Chinese civil law. To establish liability, there must be a connection between the tortious acts and tortious intent, which together caused damages to the aggrieved party and the causation shall not be broken. More specifically, the plaintiff must establish the following elements:

Tortious Act: The director or senior manager engaged in conduct that harmed the interests of the company or its shareholders.

Intent: The director or senior manager and the controlling shareholder or de facto controller acted with the intent to cause harm.

Damages: The company or its shareholders suffered damages as a result of the conduct.

Causation: There was a direct causal link between the tortious act and the damages suffered.

Only upon establishing these elements can a court impose joint and several liability. Parties seeking to prove such a claim may submit various forms of evidence, including financial documents, accounting records, work papers, company communications, emails, chat logs, recordings, and witness testimony. Where preliminary evidence suggests that the defendant is a de facto controller, Chinese courts may order the company to provide explanations and disclose relevant information. Even with the ability to obtain such information, significant hurdles remain in establishing the necessary link to establish liability.